Recognizing ageism in geriatrics

Born into a household where his parents were two generations older than him, Dr. Shabbir Alibhai has always felt that there was a special calling for him to work with older adults. It was hard for him to realize that there is a systematic bias, caused by ageism, that hinders the elders from receiving the proper healthcare they need.

The first sign was when Shabbir was deciding on his specialty in medical school. He realized that despite its great need, geriatrics—a medical specialty centered on caring for older adults—was not a popular choice among medical students.

“Geriatrics has been an overlooked area and getting people into geriatric medicine is tough. We still have unfilled residency positions every year across Canada,” says Shabbir.

Over his career, he has encountered many individuals that undervalue geriatrics. “Some would ask, ‘Why would you want to just work with old people all day? It’s not exciting’, ” describes Shabbir.

“We have to acknowledge that there is ageism in all of us.”

Shabbir completed graduate studies following his residency to address specific challenges within geriatric care. He initially looked at complex issues such as undertreatment and polypharmacy in caring for older adults.

“Older adults are not getting optimal therapy even if they are eligible for it. There is therapeutic nihilism, which is the idea that older adults are not going to live as long, so they're not going to benefit,” says Shabbir. “There is also a fear that we're likely to do more harm than good, which results in the undertreatment of older adults.”

Polypharmacy is when older adults have multiple illnesses, they can be put on multiple medications prescribed by different specialists. “At the end of the day, they can end up with 5 to 7 conditions, 6 to 10 drugs or more, and all these drugs can potentially interact with each other. But no one steps back and looks at the complexity of all of this, so it falls on the geriatricians and there are very few of us in Canada.”

Shabbir was passionate about studying these problems, but due to the large scope of the issue, he needed to find a more feasible project considering the time and money available. Supervised by Dr. Murray Krahn, who studies decision science in people with prostate cancer, and Dr. Gary Naglie, who studied patient quality of life in geriatric care, Shabbir focused on understanding how different treatment decisions can impact the quality of life for older adults with prostate cancer.

“We built a decision-analytic model to predict the best treatment option for a given patient, by incorporating the probability of dying from prostate cancer, the risk of side effects from a given treatment, the benefits of that treatment and patient preferences. And we compared that to their actual treatment to understand where the discrepancies and potential age bias were,” says Shabbir.

“It was an amazing journey and it cemented in my mind the need to study systematically aging and cancer. And that is what I have been doing ever since.”

Not only a longer life but also a better life

“For many older adults, cancer control and overall survival are important, but they also want to preserve quality of life. They want to minimize side effects, and maintain function and independence,” explains Shabbir.

One of the areas Shabbir focuses on now is to improve the quality of life and reduce the side effects of advanced therapies for aggressive prostate cancer patients. He is currently conducting a clinical trial (NCT05582772) that randomizes men with advanced prostate cancer to either a geriatric assessment and management by a geriatric oncology specialist, or remote symptom monitoring with a nurse providing weekly advice and support to manage symptoms.

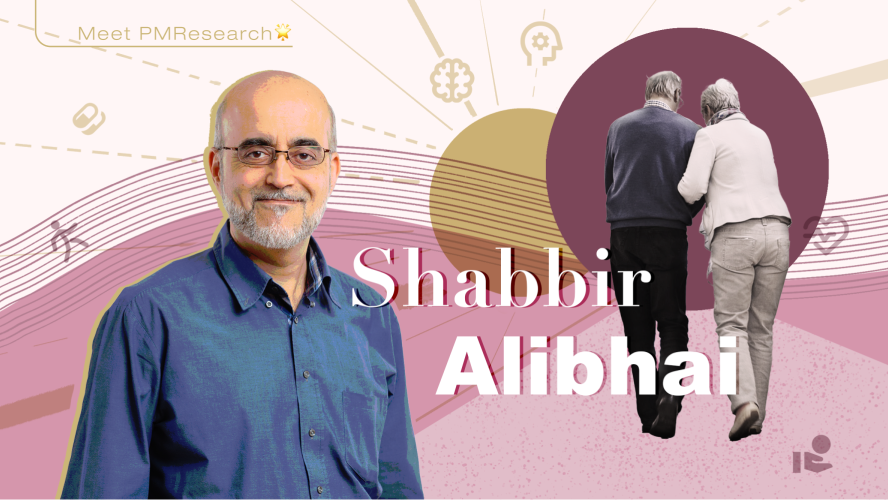

In the geriatric assessment and management treatment group, there are eight domains health practitioners look at that affect older adults’ quality of life (shown below). Meanwhile, in the remote symptom monitoring group, the focus is on managing symptoms rather than proactive assessment.

Eight domains of geriatric assessment and management.

Both interventions aim to reduce toxicity and improve quality of life but work in two different ways. Previous work has shown that they are effective in chemotherapy settings for multiple types of cancer. Shabbir is extending his research to non-chemo drugs with a focus on prostate cancer.

“Currently both interventions are pilot projects. Most of these patients are not referred to a geriatric oncology clinic to get a geriatric assessment, and there is no clinical program in remote symptom monitoring,” says Shabbir. “The study aims to assess the effectiveness and explore the possibility of providing these interventions to patients in the clinic.”

Shabbir has been instrumental in the establishment and operation of the Older Adults with Cancer Clinic, which has seen over 1,500 patients in the last eight years. Funded by The Princess Margaret Cancer Foundation, the clinic has witnessed a reduction in the overtreatment and undertreatment of patients with chemotherapy, surgery and radiation receiving geriatric assessment.

“We have been collecting information on various patients that we see in the clinic to understand different elements of what we do. What are we doing that’s working? How are we impacting treatment? And what is the economic significance of that?” From studies and an economic analysis published by Shabbir’s group, they found that geriatric assessment and management not only avoids overtreatment for patients, but also reduces costs for the healthcare system.

A key aspect to address in the clinic is the accessibility of the geriatric assessment. Despite its success, Shabbir acknowledges that the clinic only serves 10 to 20% of older adults with cancer at the Princess Margaret. And there are only a handful of such clinics across Canada. To address this, he is involved in the development of an app called Comprehensive Assessment for My Plan or CHAMP. The app aims to provide a mini geriatric assessment and offer basic recommendations, thereby extending the reach of geriatric care to more patients.

CHAMP’s rollout involves a field validation study to test its feasibility and usefulness, which is to find out whether patients and clinicians find the app satisfactory and whether its recommendations are useful. Funded by the Princess Margaret Cancer Foundation, the study is currently underway and Shabbir is also beginning to measure its impact.

Being proud of our older adults

“There are only three geriatric oncology clinics that are operating in all of Ontario and less than ten in all of Canada. Our clinic at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre is the largest one,” says Shabbir. “We are still hopelessly unable to look after all the older adults with or without cancer because our society is aging, and we have a big gap.”

The gap lies in the ageism in our society, and it calls for a shift in perspective.

“We should be proud of our older adults,” he says. “These are our parents and grandparents, who we should look up to and value them for their contributions and wisdom. They are an integral part of who we are as a society.”

Looking ahead, Shabbir envisions a future where geriatric oncology is given the resources it needs to thrive. “I hope for more clinical staff, researchers, and training opportunities to better serve older adults,” says Shabbir. “It’s difficult at times to see people grappling with diseases and dying. But I’m incredibly humbled by the courage of older people and their resilience upon hardships.”

Meet PMResearch is a monthly column that features Princess Margaret researchers. It showcases the research of world-class scientists, as well as their passions and interests in career and life—from hobbies and avocations to career trajectories and life philosophies. The researchers that we select are relevant to advocacy/awareness initiatives or have recently received awards or published papers. We are also showcasing the diversity of our staff in keeping with UHN themes and priorities.