The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted health care systems worldwide, increasing stress and burnout for health care providers. Surgical residents—doctors training to become surgeons—were especially vulnerable because of long work hours, years of training, and limited time for rest. Researchers at The Institute for Education Research at UHN identified how the pandemic exposed the challenges within the current surgical training structure that hinder residents' well-being.

The research team surveyed 82 general surgery residents at the University of Toronto about their experience with burnout, perceptions of wellness support, and overall mental health during the pandemic. The results of the survey highlighted three key findings:

● Training culture lacks wellness support—the rigid, demanding structure of surgical programs left little room for self-care.

● Limited time off—staffing shortages during the pandemic often led to cancelled vacations and time-off.

● Ineffective wellness education—mandatory wellness modules and activities felt burdensome, and residents preferred protected free time.

The study found that some barriers to wellness are embedded in the culture and structure of surgical training and were further intensified by the pandemic. Addressing these issues requires systemic changes and is essential for preventing burnout and creating more sustainable training environments for future surgeons.

Idil Bilgen and Dr. Matthew Castelo are co-first authors of the study. At the time of the study, Idil Bilgen was a medical student at the School of Medicine at Koç University in Turkey. Dr. Matthew Castelo was a general surgery resident and is currently a Breast Surgical Oncology fellow at the University of Toronto.

Dr. Tulin Cil, corresponding author of the study, is a Clinician Investigator at UHN’s The Institute for Education Research and an Associate Professor in the Department of Surgery at the University of Toronto.

This work was supported by UHN Foundation.

#Bilgen I, #Castelo M, Reel E, Nguyen MA, Greene B, Lu J, Brar S, #Cil T. Barriers to Wellness Among General Surgery Residents During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Qualitative Analysis of Survey Responses. JMIR Perioper Med. 2025 Nov 24. doi: 10.2196/72819.

# These authors contributed equally to the study.

About 300 million people globally live with some form of depression, including major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder. Although antidepressant medications can be effective for many individuals, a subset does not respond despite repeated treatment attempts. This condition—known as treatment-resistant depression (TRD)—is often accompanied by cognitive impairments, such as memory and attention difficulties, that standard therapies fail to address.

Psilocybin—a psychedelic and psychoactive compound colloquially known as “magic mushrooms”— has shown promise in improving mood symptoms in TRD in previous studies. Unlike conventional antidepressants, psilocybin can re-wire and form new connections in the brain—a process called neuroplasticity. These neuroplastic effects suggest psilocybin could also improve cognitive impairments in TRD. However, to date, research in patient populations has been very limited and results have been mixed.

In a recent clinical trial, researchers from UHN’s Krembil Brain Institute (KBI), led by Dr. Joshua Rosenblat, explored whether psilocybin could improve both mood and cognition in 26 patients with TRD. The team administered a single dose of psilocybin and assessed cognition one day and two weeks later using two standard tests: the Trail Making Test (TMT), and the Digit Symbol Substitution Test (DSST). These tests are used to measure the brain’s processing speed and executive function—skills that you use to manage everyday tasks.

Results indicated that psilocybin improved cognition modestly over time, as early as one day post-treatment. Importantly, these improvements occurred even when changes in depressive symptoms were considered, suggesting that the cognitive improvements were not just a byproduct of people feeling less depressed.

Although this was an encouraging group-level effect, only a minority of individual patients exhibited a change large enough to be considered clinically meaningful and the number of individuals who improved did not exceed what would be expected by chance alone. More studies are necessary to determine whether these changes were due to psilocybin specifically or more general factors.

Reflecting on this early-stage work, Dr. Rosenblat notes, “even though the results of our study should be interpreted cautiously, this is an invaluable first step in identifying and introducing a new treatment that could revolutionize care for TRD.” These results highlight the need for larger, controlled studies to determine whether initial findings are reproducible and whether psilocybin has a meaningful and reliable impact on cognition.

You can read the results of the original clinical trial that this study was based on here.

---

Danica Johnson is the first author of this study. She is a Graduate Research Appointee at UHN’s Poul Hansen Family Centre for Depression (formerly the Mood Disorders Psychopharmacology Unit) and a PhD Candidate at the University of Toronto’s Institute of Medical Science.

Dr. Joshua Rosenblat is the senior author of this study. He is a Clinician Investigator at UHN’s Krembil Brain Institute, and an Associate Professor and a Clinician Scientist at the University of Toronto’s Temerty Faculty of Medicine.

This work was supported by the Brain and Cognition Discovery Foundation and UHN Foundation. The Usona Institute and Braxia Health (formerly the Canadian Rapid Treatment Centre of Excellence, CRTCE) provided in-kind support.

Dr. Rosenblat receives funds from iGan, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Allergan, Lundbeck, Sunovion, and COMPASS for speaking, consultation, and research beyond this work. During the completion of this study, Dr. Rosenblat was also the Chief Medical Officer for Braxia Health (formerly CRTCE). He is no longer associated with Braxia Health. For a complete list of the other authors’ competing interests, see the publication.

Johnson DE, Meshkat S, Kaczmarek ES, Rabin JS, Brudner RM, Chisamore N, Doyle Z, Bawks J, Riva-Cambrin J, Mansur RB, Lipsitz O, McIntyre RS, Lanctôt KL, Rosenblat JD. Cognitive outcomes following psilocybin-assisted therapy in treatment-resistant depression: A post-hoc analysis of a randomized, waitlist-controlled trial. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2025 Dec 20;143:111565. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2025.111565.

On December 31, 2025, the Governor General of Canada announced 80 new appointments to the Order of Canada—one of Canada’s highest civilian honours. These appointments recognize outstanding achievement, dedication to the community, and service to the nation.

Among those recognized were UHN researchers Dr. Shaf Keshavjee, Chief of Innovation and Senior Scientist at UHN, and Dr. Allison McGeer, Clinician Investigator at UHN and Senior Clinician Scientist at the Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute at Sinai Health.

Dr. Keshavjee was promoted from Officer to Companion of the Order of Canada—the highest honour within the Order—for his transformative contributions to transplant surgery. He was appointed an Officer of the Order of Canada in 2014. Dr. Keshavjee co-developed the Ex Vivo Lung Perfusion (EVLP) system, which maintains donor lungs outside the body by mimicking body temperature and providing nutrients prior to transplantation—doubling the number of lungs available for transplant. He continues to lead research in lung preservation during transplant procedures. Dr. Keshavjee is also a Professor of Thoracic Surgery and Biomedical Engineering at the University of Toronto.

Dr. McGeer has been named a Member of the Order of Canada for her contributions to epidemiology, which have shaped national and global strategies for infection prevention. She is one of Canada’s most trusted epidemiological policy advisors and was a key figure in the COVID-19 pandemic. Her research has advanced knowledge in the fields of influenza epidemiology, prevention of health care-associated infection, and immunization. Dr. McGeer is also a Professor in the Department of Laboratory Medicine & Pathobiology at the University of Toronto.

See the full list of appointees and read the official press release.

The Order of Canada, created in 1967, recognizes individuals who have made extraordinary contributions to Canadian society. More than 8,250 people from all sectors have received this prestigious honour.

Remote patient management (RPM) programs enable patient care to be accessible from anywhere. For heart failure—a serious condition in which the heart does not pump blood as well as it should—remote management can help track health data, detect early warning signs, and alert care teams when interventions are needed. In a new study, researchers at UHN found that well-designed remote management programs can make heart failure care more equitable and accessible.

Medly is a digital therapeutic platform for heart failure management and care developed at UHN by Clinician Investigator Dr. Heather Ross and Senior Scientist Dr. Joseph Cafazzo. The platform was developed in concert with UHN's Peter Munk Cardiac Centre and Centre for Digital Therapeutics, as well as the Ted Rogers Centre for Heart Research. Medly is an RPM program that enables patients to record symptoms, heart rate, blood pressure, and daily weight on a mobile device—most often a smartphone—and receive personalized self-care messages generated by a clinically validated algorithm.

The program was designed to be used with any smartphone, regardless of the model or operating system. All patients are eligible as long as they are able to use Medly as intended (e.g., stepping on a weight scale). The program also provides equipment and connectivity to those who need it, without charge or additional requirements to qualify.

Although programs such as Medly are becoming more common in heart failure care, questions remain about who can actually access them. To assess this, a new study examined validated markers of marginalization—the process by which individuals and groups are prevented from fully participating in society—among patients with heart failure enrolled in Medly. The study also measured how many patients needed partial or full equipment support from the program and where patients lived in relation to the hospital.

Using a measurement called the Ontario Marginalization Index (ON-Marg), the researchers identified the levels of marginalization across neighbourhoods where Medly patients lived over five years. They found that Medly was used by patients across all levels of marginalization. They also found that out of 1115 patients, 38% required at least some equipment from the program to participate and that the program served patients both near and far from their treating hospital.

The findings highlight that providing equipment, minimizing exclusions, and ensuring compatibility with any device can make RPM programs like Medly broadly accessible and help overcome barriers such as cost or lack of technology.

Overall, the study found that thoughtfully designed remote monitoring programs can make heart failure care more equitable and accessible.

Dr. Mali Worme, Clinician Investigator and staff cardiologist at UHN, Clinician in Quality Improvement and Innovation, and Assistant Professor at the University of Toronto, is the first and corresponding author of the study.

Dr. Heather Ross, Clinician Investigator at UHN, Division of Cardiology at UHN’s Peter Munk Cardiac Centre, and Professor in the Institute of Medical Science at the University of Toronto, is the senior author of the study.

This work was supported by UHN Foundation.

Please see the manuscript for any competing interests.

Worme M, Kim B, Ware P, Seto E, Simard A, Ross H. Equity in Heart Failure Care: Examining the Area-based Marginalization Status of Patients in an RPM Program. Can J Cardiol. 2025 Nov 20:S0828-282X(25)01430-8. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2025.11.021. Epub ahead of print.

Researchers at UHN’s Princess Margaret Cancer Centre have found that inactivation of the TET2 (Tet methylcytosine dioxygenase 2) gene in immune cells improves the response of immunotherapy—a type of treatment that helps the immune system attack cancer cells—in certain cancer models. These results could lead to a marker that predicts how well immunotherapy for cancer will work.

TET2 is an important regulator of gene expression and is frequently altered in clonal hematopoiesis (CH), a condition in which a mutated blood stem cell makes many identical copies of itself. Although CH can lead to cancers such as leukemia, it is still unclear how CH affects tumour biology, cancer outcomes, and response to treatments such as immunotherapy. TET2 inactivation is associated with improved function of immunotherapy involving T cells—immune cells that find and destroy infected or abnormal cells—and can boost immunity.

These links to immunity led the research team to investigate how TET2 mutations impact responses to cancer immunotherapy approaches like immune checkpoint blockade (ICB)—in which drugs inhibit proteins that are normally responsible for keeping the immune system in check. This then enables immune cells to kill cancer cells.

Using preclinical cancer models, the study found that TET2 mutations in blood-forming cells enhanced the ICB response, but only in the presence of special immune cells that help fight infections and cancer, including phagocytes, CD4+ T cells, and CD8+ T cells. TET2-mutant immune cells respond to ICB therapy by shifting away from tumour-promoting states toward tumour-fighting states. This mutation led to the activation of T cells and led to the development of stronger “memory” to recognize cancer in some immune cells, along with fewer signs of fatigue or suppression in these cells.

Clinical data reinforced these findings: tumours from colorectal cancer and melanoma patients with TET2-related CH showed higher immune activity. In melanoma patients receiving ICB, those with TET2 mutations were six times more likely to benefit from treatment.

These results suggest TET2 mutations could serve as a marker for personalized immunotherapy, potentially guiding treatment decisions in the future. A deeper understanding of how TET2 inactivation improves immunotherapy responses could someday lead to new, synergistic treatments.

Dr. Vincent Rondeau, Postdoctoral Researcher at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, is the first author of the study.

Dr. John Dick, Senior Scientist at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University Professor at the University of Toronto, Helga and Antonio De Gasperis Chair in Blood Cancer Stem Cell Research, and Professor in the Department of Molecular Genetics at the University of Toronto, is the co-corresponding author of the study.

Dr. Robert Vanner, Affiliate Scientist at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, Clinician Scientist in the Division of Medical Oncology and Hematology at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, and Assistant Professor at the Institute for Medical Science at the University of Toronto, is the co-corresponding author of the study.

This work was supported by Merck Canada Inc., the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society of Canada, the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, the PSI Foundation, the Douglas Wright Foundation, The German Cancer Research Center, the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research, Terry Fox Research Institute, the Canadian Cancer Society, the Government of Ontario, the Ontario Ministry of Health, the Canada Research Chairs program, and The Princess Margaret Cancer Foundation.

Dr. Robert Vanner and Dr. John Dick are co-inventors of a patent, ‘Clonal Hematopoiesis as a Biomarker’. Dr. Dick receives revenue from patents licenced to Trillium Therapeutics Inc/Pfizer and receives a commercial research grant from Celgene/BMS.

Rondeau V, Bansal S, Buttigieg MM, Zeng AGX, Chan DY, Chan-Seng-Yue M, Jin L, McLeod J, Kates M, Donato E, Stelmach P, Vlasschaert C, Yang Y, Gupta A, Genta S, Sanz-Garcia E, Shlush L, Ribeiro M, Butler MO, Abelson S, Minden MD, Saibil SD, Chan SM, Rauh MJ, Trumpp A, Dick JE, Vanner RJ. Response to Immune Checkpoint Blockade is Enhanced in the Presence of Hematopoietic TET2 Inactivation. Cancer Res. 2025 Nov 11. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-24-3329. Epub ahead of print.

A University of Toronto (U of T) based research team, co-led by Dr. Jennifer Gommerman from U of T's Temerty Faculty of Medicine and Dr. Valeria Ramaglia from U of T and UHN’s Krembil Brain Institute, has discovered how progressive multiple sclerosis (MS) develops. Their findings also point to a promising biomarker—a measurable biological sign of disease—that could help clinicians better identify, and eventually treat, individuals living with this debilitating form of the disease.

Progressive MS is notoriously difficult to diagnose and treat because its underlying inflammation occurs deep within the brain and is challenging to measure in living patients. The findings of this study offer a way to better understand this hidden process and determine which patients are most likely to benefit from current or emerging therapies.

MS is a degenerative autoimmune disease. An autoimmune disease occurs when the immune system attacks healthy cells or tissues. In the case of MS, it attacks myelin—the protective insulation surrounding nerve fibres in the grey matter of the central nervous system (CNS), including the brain and spinal cord. This damage disrupts neuron-to-neuron communication and leads to symptoms such as muscle weakness, vision problems, pain, and changes in mood or behaviour. In progressive MS, these symptoms worsen over time, leading to increasing disability.

MS is characterized by “compartmentalized” inflammation, which occurs when the immune response that causes inflammation moves from the surrounding tissues to specific compartments of the CNS. In progressive MS, inflammation has been observed in the meninges—the thin, protective layers that surround the CNS. This inflammation can lead to the formation of small lymph node-like structures made of clusters of immune cells, including B cells, in the meninges.

Although previous studies have linked meningeal lymph node-like structures to grey matter injury in progressive MS, the mechanism connecting them remained unclear.

“To close this knowledge gap, we recognized we needed to innovate,” says Dr. Ramaglia. “Utilizing a novel lab model that accurately reproduced the grey matter injury seen in progressive MS was an essential first step."

Using their new model, developed at U of T, the team examined how immune proteins behave during grey matter injury. The results revealed striking changes in two immune proteins: CXCL13 and BAFF, proteins that help control immune cells. At the onset of injury, CXCL13 increased by 800-fold, while BAFF levels decreased significantly.

When the team introduced a Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor (BTKi)—a drug that blocks the BTK protein, which mediates immune cell activity—the effects of brain injury were reversed: CXCL13 decreased and BAFF increased, restoring a ratio of CXCL13:BAFF comparable to that seen in uninjured models. BTKi treatment also reduced both the number and size of lymph node-like structures in the meninges. Together, these results revealed that meningeal inflammation and grey matter injury are driven by a balance of CXCL13 and BAFF and depend on BTK signalling.

These discoveries led the researchers to propose that the CXCL13:BAFF ratio could serve as a biomarker for meningeal inflammation and possibly compartmentalized inflammation deeper in the brain. To test their hypothesis, the Gommerman-Ramaglia team examined brain tissue samples from individuals with MS. They found that patients with a greater number of immune cells in the brain’s protective layers—indicating more severe inflammation—also had elevated CXCL13:BAFF ratios.

A separate analysis of MRI data from another patient group further supported this finding. Individuals with parametric rim lesions (PRLs), brain lesions that are another marker of progressive MS, also showed higher CXCL13:BAFF ratios compared to individuals without these lesions.

Although further studies are necessary, if validated, this ratio may give clinicians a practical tool to identify patients experiencing the type of inflammation associated with progressive MS.

By unravelling the circuitry that contributes to progressive MS, this research offers insights that could help shape future treatment strategies. It identifies possible new avenues for therapeutic development, as well as sheds light on factors that may explain why existing treatments have been less effective in progressive disease. The team also believes it could support recruitment for ongoing clinical trials of BTK inhibitors and help improve how patients who are most likely to respond to a treatment are identified.

“With Canada having one of the highest rates of MS worldwide, it seems fitting that this advancement in our understanding is homegrown”, notes Dr. Gommerman.

As she builds her own research program at Krembil Brain Institute, Dr. Ramaglia continues to collaborate with Dr. Gommerman to explore how the ratio could advance precision medicine in MS. Building on this study, Dr. Ramaglia plans to focus next on investigating whether the CXCL13:BAFF ratio can be used to help predict which individuals with early MS may go on to develop the progressive form of the disease. This could mean earlier diagnosis and better treatment options for people living with progressive MS.

Dr. Ramaglia credits Dr. Gommerman’s mentorship as instrumental to her growth as an independent scientist and helping to set her up for success as she transitioned to her new role as an independent Principal Investigator at Krembil Brain Institute.

*Check out the University of Toronto Temerty Faculty of Medicine’s feature on this work here.

---

The first author of this study is Dr. Ikbel Naouar, a Senior Research Associate at the University of Toronto.

Drs. Valeria Ramaglia and Jennifer Gommerman are co-senior authors of this study. Dr. Ramaglia is a Scientist at UHN’s Krembil Brain Institute and an Assistant Professor of Immunology at the University of Toronto. Dr. Gommerman is a Professor of Immunology at the University of Toronto, and a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Tissue-Specific Immunity.

This work was supported by the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, MS Canada, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the United States Department of Defense, and UHN Foundation. Support from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society and the United States Department of Defense was given to Drs. Gommerman and Dr. Ramaglia. Support from MS Canada and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research was given to Dr. Gommerman.

Dr. Gommerman shares a patent for the treatment of autoimmune disease, such as multiple sclerosis, or inflammation, which includes at least the administration of B-cell activating factor (BAFF). Drs. Cenni and Nuesslein-Hildesheim are employees of Novartis. For a complete list of competing interests, see the publication.

Naouar I, Pangan A, Zuo M, Raza SA, Champagne-Jorgensen K, Patel J, Wang A, Pu A, Ward L, Ahn JSY, Sayeed FN, Zhu J, Pössnecker E, Cenni B, Nuesslein-Hildesheim B, Browning JL, Probste A-K, Reich DS, Gommerman JL*, Ramaglia V*. Lymphotoxin-dependent elevated meningeal 1 CXCL13:BAFF ratios drive grey matter injury. Nat Immunol.

Slipping on ice is a major cause of winter injuries and a costly burden to the Canadian health care system. A new study from UHN’s KITE Research Institute shows that even top-rated winter boots cannot fully prevent slips, highlighting the need for additional safety measures.

As winter footwear design advances, researchers at the KITE Research Institute WinterLab evaluate slip resistance using a standardized test to measure how well boot sole technologies reduce the risk of slips and falls. Using a specialized platform that recreates winter conditions, researchers developed the Maximum Achievable Angle (MAA) test, which measures the steepest slope an individual can walk on without slipping. This provides a clear measure of slip resistance, but ice remains unpredictable and uniquely hazardous compared to other surfaces.

To better understand slip risk on icy surfaces, the research team recruited 27 participants to walk on an icy walkway while wearing a safety harness and 11 different winter boot models from popular brands, including Timberland, Merrell, and WindRiver. Boots were categorized as poor, moderate, or good slip resistance based on their original MAA score.

The results were striking. Analyzing over 8,500 steps, researchers found that nearly 12% resulted in a slip—approximately one slip every nine steps. Boots with poor ratings had a 36% slip risk, while even the highest rated boots still showed a 4–5% slip risk. Even advanced designs could not fully prevent slips.

These findings highlight that ice remains far more hazardous than most surfaces. While choosing boots with higher slip-resistance ratings is important, additional measures such as timely ice clearing, heated pavements, and safer walking techniques are needed to reduce winter injury.

This research group provides slip-resistance testing of winter footwear for manufacturers. Insights may inform the design of future commercial or service-based applications.

Davood Dadkhah, first author of the study, is a PhD candidate at UHN’s KITE Research Institute in the lab of Dr. Tilak Dutta.

Dr. Tilak Dutta, senior author of the study, is a Senior Scientist at UHN’s KITE Research Institute. At the University of Toronto, Dr. Dutta is an Associate Professor in the Institute of Biomedical Engineering and the Institute of Rehabilitation Sciences.

This work was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and UHN Foundation.

Dadkhah D, Ghomashchi H, Dutta T. Determining the risk of slipping on level ice using winter footwear with varied maximum achievable angle slip-resistance performance. Appl Ergon. 2026 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2025.104678. Epub 2025 Oct 31.

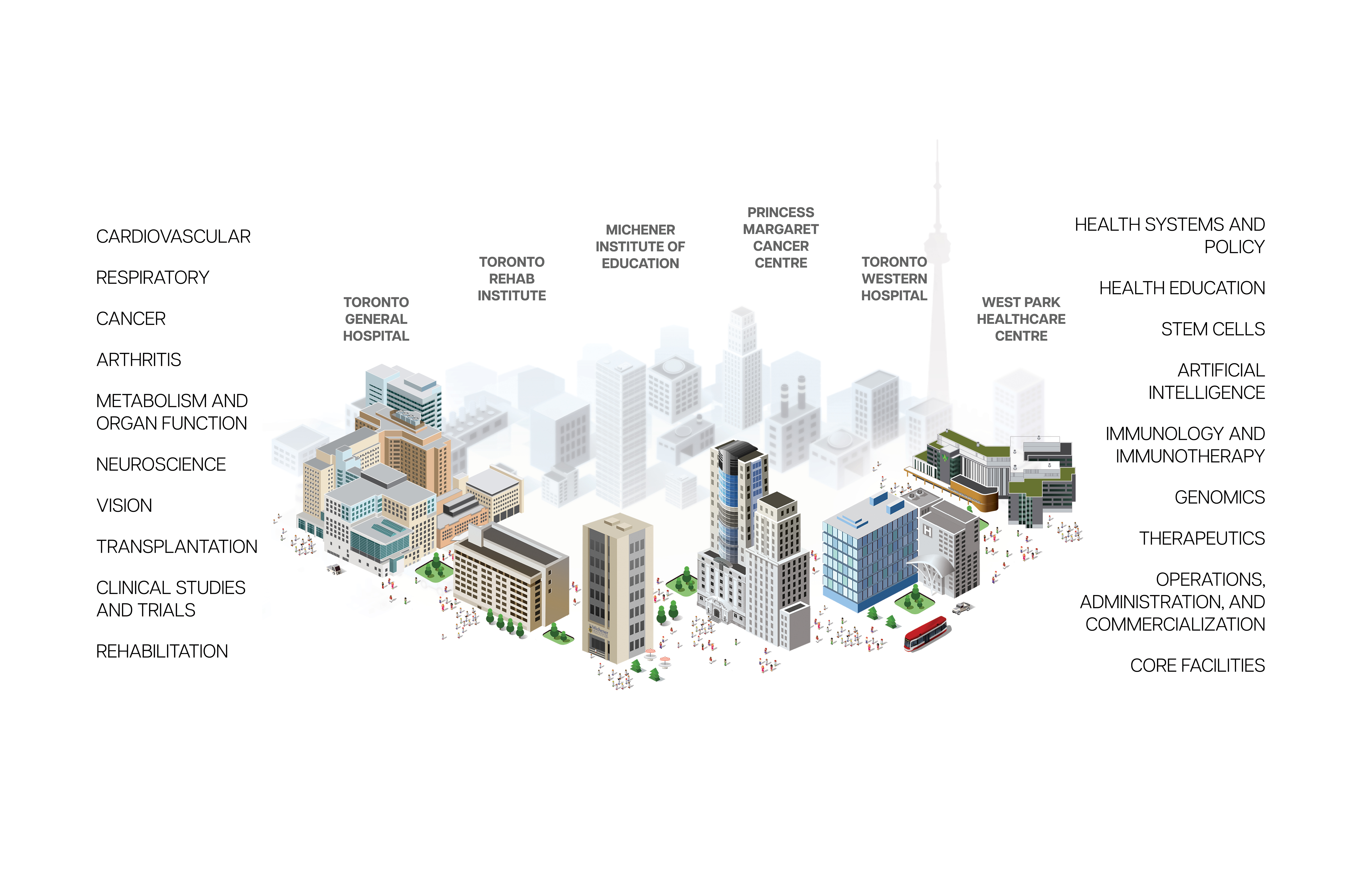

Research at UHN takes place across its research institutes, clinical programs, and collaborative centres. Each of these has specific areas of focus in human health and disease, and work together to advance shared areas of research interest. UHN's research spans the full breadth of the research pipeline, including basic, translational, clinical, policy, and education.

See some of our research areas below:

Research at UHN is conducted under the umbrella of the following research institutes. Click below to learn more: